“A manager’s output = The output of his organization + The output of the neighboring organizations under his influence. Why? Because business and education and even surgery represent work done by teams.” – Andy Grove, CEO of Intel, writing in High Output Management

Emphasis mine. When people become people managers, they are often excited about managing their new team. There’s a lot of new stuff to figure out — how do I run a one-on-one? Or a performance review? What happens when I have to give hard feedback for the first time, or even put someone on a PIP? — and most of the advice produced for new managers talks about that stuff because it’s so obviously new.

And that’s a problem, because your job as a people manager is not, fundamentally, to manage your team. It’s to increase the value created by the organization, and you do that via Andy Grove’s formula.

In “Becoming a people manager is not a promotion,” I wrote about one of the reasons people want to become managers:

You wish that you had better managers when you were on your way up, and this is your opportunity to be that manager for someone else. You may have a mental picture of the report-manager relationship where you teach your report, coach them through things you once struggled with, and generally be the guiding force you wish you had yourself.

There are three misconceptions about management at play, all of which are enticing because they carry with them a grain of truth.

Management is about teaching. As a management, increasing the level of subject matter expertise on your team is a potentially high-leverage activity. Spending “classroom time” teaching your reports directly is not, because it will take away from the less obvious and more important information gathering that is now your job.

Management is about production/organization. New managers often want to create processes and workflows for their teams. I wrote about why this is a bad idea in “Don’t trust the process,” but the TL;DR is that process is for optimization of well-understood tasks that are proven winners, and is massively inefficient when used for anything else (because it creates machinery you have to change).

Management is about empathy. You need your team to trust you. You need to give hard feedback with a kind heart. You need to be able to have difficult conversations. All of this is true, and psychological safety is one of the most important factors affecting team performance — but your job is not for your team to like you, and it’s possible (and dangerous) to lose sight of that.

Through a combination of good mentors and a whole lot of reading, I feel like I was able to avoid the dangerous part of these misconceptions. In each case, the danger is that you focus too much on your own direct reports — when, as a manager, you should spend more time with other managers in the organization.

I have seen VP-level marketers who were beloved by their teams get fired for this reason. Take it seriously.

Your “first team,” and how communication changes as a manager

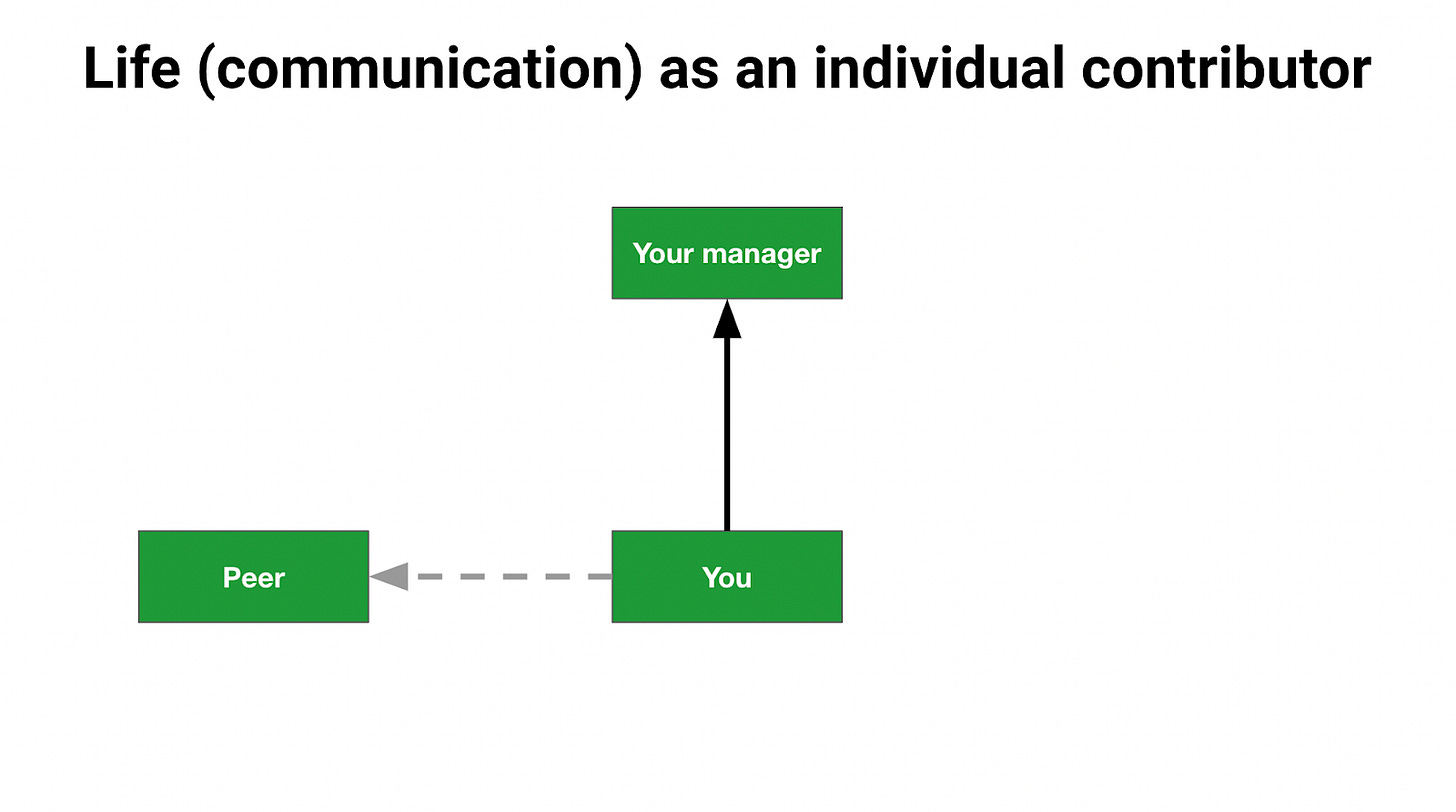

This is life as an individual contributor.

You talk to your manager often and you talk to your peers sometimes. There are exceptions, but for the most part your scope of communication is pretty limited and there aren’t a ton of people to talk to on a day to day basis.

When people get promoted to manager, here is what they often expect communication to look like.

Makes sense, right? Not much has changed; you just moved up a level and so there’s one other level of communication. But you still talk to your boss regularly and your peers sometimes.

No.

You have moved up one level, but the air on that level is different. As a manager, you’ve entered the communication strata of your organization, and a massive part of your work is the gathering and sharing of information in pursuit of projects (and output) with other teams.

You need to work with your peers at least as much as you work with your direct reports. When you create plans, processes, structures, info summaries, OKRs, or anything else to share with your boss, you can expect that your boss will also share it with their peers and your boss’s boss — which means anything you create has to be understandable by anyone in the organization with you being their to explain it to them.

Every company has these webs of communication, and you are now part of it.

That diagram has 7 boxes. One of them is you. It could have way more, depending on how many other peers you and your boss have.

Now imagine you spend most of your time with your direct reports.

You’ve cut yourself off from the lifeblood of great management, which is information. Here’s Andy Grove again, explaining why:

“Your decision-making depends finally on how well you comprehend the facts and issues facing your business. This is why information-gathering is so important in a manager’s life. Other activities—conveying information, making decisions, and being a role model for your subordinates—are all governed by the base of information that you, the manager, have about the tasks, the issues, the needs, and the problems facing your organization.”

You can increase the performance of your team by having them spend more time on the most important things and by coordinating with other teams on those things to get more resources. If you don’t know what people on other teams want or what they’re working on, you aren’t going to be much more than a beefy individual contributor. You won’t know how to guide your team’s effort or help them make decisions, and the overall impact of your team will be minimal even if you are still producing great work.

I have never read a book by Patrick Lencioni, but people tell me the phrase “first team” is most often associated with him. Your peers in your organization — other managers — are your first team. You should spend most of your time working with them. Your direct reports are your second team.

You need to build your first team and also help your direct reports build their own first team

This is worthy of an entirely separate article, but what does it look like to build your first team? And also — how can you make your direct reports less reliant on you, so that you don’t get pulled into IC work too often?

In both cases, you need to create a council.

You and your peers need to be able to coordinate with each other. In a sufficiently large organization, that probably means organizing an ongoing conversation where all of the relevant peers are in the same room. If you and your peers have the same boss, that boss really ought to have created a meeting like this already (just like you are about to do for your direct reports). The company I’m at right now is not large, but the leadership team meets weekly and has several other async lines of communication.

Regardless of organizational size, you need to have one-on-ones with your peers. Even if there’s not always a clear mission of the meeting, you need to build the relationship. When you ask for resources, there’s no way to replace the good will of 6 months of conversations other than having spent the previous 6 months having conversations. If nothing else, your goal in one-on-ones is to make friends and understand what people want, because it’s this information that helps you make decisions.

While you work on your first team, you also need to help your direct reports make decisions. I’m stunned by how many managers operate their teams as a series of one-to-one relationships — no communication at all between their direct reports.

Hey! That’s not a team! It’s a group of people who work on similar things without talking to each other.

Your reports will also be more effective if they have strong relationships with their peers, so you need to structure your communication in ways that puts them in contact with each other (team meetings, Slack channels, whatever) and ideally structure your projects so that they require teamwork. The more your team works together to solve problems, the less often they need to bring problems to you and the more time you can spend with your first team.

Ok let’s TL;DR this whole thing: work with your peers at least as much as you work with your direct reports. This is a simple insight that surprises new managers (it surprised me, although luckily before I made the mistake). Focusing too much time on direct reports is what leads to underperformance and career risk; spending time with your peers leads to growth, results, and getting what you want.

This might be one of the most important articles on management that people could read. Honestly. For me, it reads as a post-mortem of mistakes that I made in my 3 previous leadership positions. I can't imagine how things might be different if I'd had these insights sooner. Incredibly generous thoughts, as always, Benyamin.