Controversial career advice: Skills first, then company (also: how to choose a company)

You need a company with a great market and a great product that’s *essential* to the people who use it. Take your skills there.

An obvious thing that goes unsaid in advice to “advocate for yourself” is that it is a lot easier to advocate for yourself if you have 1) a valuable and uncommon skill set and 2) experience with that skill set in environments that forced you to get through challenges common to most companies.

In my first full-time job out of college, I was hired to spit out 300-500 word search-optimized product pages at a rate of ~4 per day. That was it. A year in, I could hit that target easily and started to lead SEO/content strategies while working directly with clients. I had also started a side project that blew up on Reddit three times and pulled 30,000 visitors a month.

My skill set had evolved, so I went to advocate for myself and asked for a raise. After about 6 months of negotiating, my salary went from $38,000 to $46,000. 6 months after that I left the agency world for a job in SaaS; the hiring manager was impressed despite the lack of tech in my background, and I walked out of the interview sure I’d get the offer.

Thereafter I saw substantial increases in my responsibilities and salary every ~9-12 months. Some of those increases I asked for, some were given to me. None took 6 months of stonewalled negotiating.

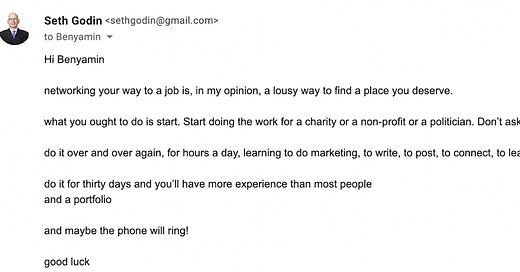

A month before all of this started at the marketing agency, I got this reply to an email I sent to Seth Godin.

“Working for free” has become an unpopular idea (with good reason, in many cases), but that wasn’t what stood out to me about Seth’s email.

What he essentially said to me was “get really really good. When you get really really good, you get more opportunities and you can do more with the ones you get.”

I took his advice, or did my best to. But after I built up some skills, I still had career trouble that wasn’t solved by just being willing to advocate for myself.

I think advocating for yourself is important. Probably no one else will advocate as hard as you will.

But I also think it’s not really the place to start as you think about growing your career. Self-advocacy of the wrong things in the wrong context is hard; advocacy when you’ve built up the right skills and experience is easier — people will start to come to you with opportunities, instead of you needing to always go out and find them.

Recently, people early in their careers have started to come to me for career advice. I tell them to focus on these two things:

Start with skills. Learn something valuable and hard to understand. Think deeply about your work. Practice. Don’t just repeat; practice. Rack up some results related to skills you learn, then learn how to tell other people about those results. Your skills are the first foundation that will carry you upwards in your career.

Follow up by working at the right company. Some industries and types of companies give you many more opportunities to learn than you will get anywhere else. Jobs at these companies are great because they will force you to learn more rare and valuable skills and they will make it easier for you to get your next job.

Skills are your foundation; you don’t actually need to have a “career path”

The skill that I started with was writing articles. I then quickly added SEO and copywriting. After that I started to pick up pieces of other things — analytics, marketing automation, email, conversion rate optimization.

When I got my second job, I could say “my side project gets more traffic than your entire website, and I can do it for your website too.” Not in those words, because I’m not *that* much of an ass, but it was a pretty good pitch and I got hired quickly. Once I was hired, I had a lot of latitude to do things that fell within my skill set.

A lot of the early-career folks I’ve spoken to or managed ask questions about “career path.” I think there are industries where career paths are relatively rigid, but for the most part it’s the wrong question — careers are nonlinear, the path is a long and winding road that leads to your door, and you don’t actually have to decide what your door is before you get there.

Your manager can’t define your career path. Your company’s “career path” diagrams are always at least 50% bullshit because they:

Try to turn something nonlinear into a straight line

Have the unspoken assumption that you will stay at your company to move up the path, when most people come in at a level and move up just 1 more level before switching

The predefined path that a company presents will change for top performers — companies will do a lot to keep really good people, even if it means breaking their own rules

The criteria for moving up in a career path aren’t total bullshit, but they are mostly irrelevant unless the company is performing really well — opportunities to advance are limited by the opportunities available at the company in the first place.

And there’s another reason, not related to your company but extremely important to you as you think about the next steps of your career:

The world is going to change, and you can’t predict exactly how.

What if you choose a linear road and it leads to you being a Blackberry manufacturer in 2016? The job I have now didn’t exist 5 years ago, and my next job probably won’t exist until 5 years from now.

Instead of imposing a comforting-but-false structure on your career, I tell people to invest in probabilities. I know that some skills are never going away — anything I can learn about data, finance, copywriting, customer research, and people management will be useful to me forever. Even if I don’t know exactly how I’ll use those skills now, I trust that having them will let me make new connections and flex into new areas of expertise.

This happens often, actually. People who spend a lot of time learning find that their knowledge has no outlet, and that knowledge will sit (maybe for years) until it suddenly becomes useful. My environment until recently had basically no use for a skillset in qualitative research design, but I have some skills there. When I switched jobs, qualitative research was one of the first things I needed, and the potential of that knowledge was unlocked.

Don’t worry about your career path, and only worry a little bit about your title and the trappings of the career ladder. It’s easy to be seduced by things you don’t actually want because you perceive them to be the elements of success. I meet plenty of people who say they want to run strategy or become people managers even though their actions show that they are most passionate when working in the details as individual contributors.

And that’s ok. When you shift from “what should I be achieving” to “what do I actually *want* to learn,” it’s easier to step away from things that are not for you.

This essay isn’t about the nitty-gritty of skilling up, but here’s the gist of how to get better:

Find skills at the intersection of “genuinely interesting to me” and “will be valuable for a long time.” You want skills that are important and held by few people, but you won’t really dedicate yourself to those skills unless they interest you personally.

Focus on truth-seeking, not “philosophies.” Marketing (my field) is rife with philosophies. “Marketing is about connection,” “people want to see your brand's purpose.” Value statements should be a red flag while you’re learning; look for truth evidence (not statements). In the case of marketing, “here is the evidence about how people actually consider and buy products.”

Learn from the best. Not from the “good.” Look for the people who are the best at what you want to learn. Too many people learn from folks barely more experienced than them, and it makes it harder to build deep understanding and see really expert-level connections. The best will not always teach classes, but you can still learn from their work.

Look for principles, instead of “this is good” or “this is bad.”

Practice.

Company is your opportunity to use the skills you have and develop skills you never thought you’d learn

Here’s why you should think really hard about which companies you work at:

The right company has resources to support your growth. But more precisely, it’s growing at the same time as you are growing — it’s small enough that there’s room for you to stretch into new areas and responsibilities, but growing fast enough that your opportunity isn’t limited by resources.

You will learn things that you don’t even realize you are learning. You won’t recognize how valuable it was to sit in some random finance meeting or negotiation between sales and product until 4 years from now at your next job when a similar situation pops up.

Future companies will really, really value the experience you have at companies one level of growth up from where they are. You will have the “been there, done that” experience that makes you incredibly employable and results in opportunities coming to you.

Just the other day I had a conversation with someone thinking about how to expand their marketing and sales into Europe. This isn’t my area of expertise and it’s not what I do — but at my last job I sat in on tons of conversations about how we localize the sales process into multiple languages, what types of vendors we needed to use (and for what), which regions can get by with English content, headcount, and all sorts of other details that I wasn’t intimately involved in but got to see.

I’m still not a localization or international ops expert, but I know more about what questions to ask and have some knowledge of an area that is uncommon to be knowledgeable of (especially for someone with my background/career stage).

I used to think that experience was overrated, and that everything you needed to know you could learn by intentionally practicing. Now I think that knocking experience is a young person’s game.

“Most people do not accumulate a body of experience. Most people go through life undergoing a series of happenings, which pass through their systems undigested. Happenings become experiences when they are digested, when they are reflected on, related to general patterns, and synthesized.” – Saul Alinsky

I regularly encounter situations where I think “oh, this is like that time when…” and realize that I took away lessons from my experience that I never even realized I was learning. “This is how we dealt with X,” when X wasn’t even a problem my department encountered and that I rarely thought about — but knowing how it was addressed is still useful.

Those are the opportunities that you get at the right company. You (and I) have a predilection to pursue certain types of knowledge. I like learning about copywriting and statistics and psychology, but knowing more about finance and customer support and operations unlocks new ways of thinking and lets me spot new connections.

At the right company problems will come up that need to be solved. And since no one actually knows how to solve them you will be able to get your hands dirty. Your environment accelerates your learning.

Hopefully I convinced you. When it comes to choosing a company, what size should you look for?

Not a startup. You can get your hands on a little of everything at a startup, but you’re very likely to be constrained by the growth of the company. Can’t be a people manager if there’s no money to hire people, etc. etc.

Not a huge company. A huge company has more specialization, and with that come more rigidities. You are more likely to be forced into a rigid career pathing process and less likely to pick up the smattering of experience that lets you jump ahead quickly.

Growth stage. 50-200 employees is an approximate range (but some consumer orgs can be small and still fit). You want a company that’s growing really fast and needs to find answers really fast, and has plenty of resources to put towards finding those answers. You’ll have to get your hands into a range of projects, which gives you experience in those areas even though you’ll eventually hire someone to specialize in them.

The simplest way to spot the right stage of company is to look for companies that are already growing. Bootstrapped companies don’t always have their announcements covered, but companies who have just taken a moderate series A are likely to be good candidates, and it’s easy to find that information.

Once you have candidate companies, you ask these three questions:

How big is the market for this company, and is it growing?

How good is the product, and is there product/market fit?

How essential is the product to people who use it?

You want a big market, because it’s a lot easier to grow when there are a lot of people who could buy your product. You can make a lot of mistakes and still grow quickly — and companies with small markets will hit growth plateaus sooner than you expect.

You want a great product, obviously. But more than that you need a product that is essential to its consumers. You don’t want a nice-to-have — you want something that your customers can’t live without. Again, this gives you room to make mistakes and still grow crazy fast.

I believe in self-advocacy. I also believe that it is easier to advocate for yourself when:

You are really, really, really good at what you do

You have experience in situations where not a lot of people have experience

Set aside career paths and titles and status and what you “should” want, and focus on the ingredients of a career where you can make your own choices.