On imposter syndrome and the speed of the world

Wherein I decide that I was an imposter, for at least a little while

“When faced with incomprehensible events, there is often no substitute for acting your way into an eventual understanding of them.” — Karl Weick

Babies are so goddamn stupid. Seriously, they can barely do anything, and the stuff they can do they screw up in hilarious ways. Half the reason kids are so adorable is how dumb they are, and the other half is their chubby little cheeks. They’re so dumb that there’s an entire subreddit called /r/KidsAreFuckingStupid, and it has 2.1 million subscribers.

The top post of all time is “My girl does a 50 meter run-up to kick a ball,” and you can guess what happens.

When I think about the beginning of my career, I think about how the monstrously stupid stuff kids do has great internal logic. Like when a kid asks “do ants get cold because they don’t wear jackets,” you can see how they got from point A to B, and also that the map they’re using is drawn in crayon and covered in spaghetti sauce. When I was 3 and wanted to do something I knew wasn’t allowed, I would take my parents by the hand and walk them into another room. And yes, they still love to tell that story.

I started my career as a 22 year old paid to give advice to 40+ year old marketing managers at huge biotech and medical device companies. Often that advice was just to point to the output of some tool (see look! Here’s how many people search for “high-performance liquid chromatography”), but sometimes I was asked for my opinion and I can only hope what I said didn’t sound like “I think we should knit sweaters for ants.” I remember one call with a huge REIT where the person on the client-side was an MD/PhD/MBA, which meant they had more years of education than I had been alive.

I’m can’t remember if I did say anything quite that dumb, and for that I have to thank my imperfect human memory and its rose-tinted glasses — because I’m sure it happened. I’ve recounted the experience to folks who empathized, and said “imposter syndrome is hard.” No! I jumped into a field with no training, wholly ignorant of everything! I didn’t know the words and phrases people used, how different types of projects get done, even what people talk about in an office around the table at lunch.

This wasn’t imposter syndrome. I was an imposter!

In 1845, an expedition led by British captain Sir John Franklin set sail for the Arctic circle. The ship immediately became icebound and unable to move. The crew survived off rations, as best they were able, for over a year before being forced to abandon the ship and brave the cold at King William’s Island. Two dozen, including Franklin, were already dead, and it didn’t get better for the rest of them.

Franklin and his men were like me. They explored an unfamiliar terrain in which they had no knowledge, and I launched into an unfamiliar career where I had no understanding.

Oh, except they all died.

Yeah, so the remaining crew set out to survive in the Arctic, gradually resorted to cannibalism, and then froze or starved to death.

What the expedition illustrates is that people are remarkably bad at figuring things out from scratch. Adults have more knowledge than babies, but adults can still say stupid, internally consistent things when they don’t have the right context for the situation. Franklin and his men starved in the Inuit’s most fertile hunting grounds — the Netsilik name for the main harbor is literally “lots of fat” — because their 105 well-trained brains couldn’t make any sense of their new situation alone, even though they had 3 years to figure it out.

Maybe this is an unfair comparison, but no one would look at the crew and say they suffered from imposter syndrome.

I didn’t want to be an imposter anymore, and I prefer to not starve/freeze to death in the arctic. Early on, I put in the work to learn my shit, and I chose the approach that the crews of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror (really? They named their ship the Terror?) should have used. I sought out the absolute best in the field and learned from them.

Anthropologist Joe Henrich recounts the story of Franklin’s lost expedition in his (imo poorly named but excellent) book The Secret of Our Success.

“Let us briefly consider just a few of the Inuit cultural adaptations that you would end to figure out to survive on King William Island. To hunt seals, you first have to find their breathing holes in the ice. It’s important that the area around the hole be snow covered — otherwise the seals will hear you and vanish. You then open the hole, smell it to verify that it’s still in use (what do seals smell like?), and then assess the shape of the hole using a special curved piece of caribou antler. The hole is then covered with snow, save for a small gap at the top that is capped with a down indicator. If the seal enters the hole, the indicator moves, and you must blindly plunge your harpoon into the hole using all your weight. Your harpoon should be about 1.5 meters (5 ft) long, with a detachable tip that is tethered with a heavy band of sinew line. You can get the antler from the previously noted caribou, which you brought down with your driftwood bow. The rear spike of the harpoon is made of extra-hard polar bear bone (yes, you also need to know how to kill polar bears).”

Henrich’s thesis is that humans are sort of smart, but not in the way that lets us wade into unfamiliar water, look at the resources at our disposal, and — in a flash of insight — figure out how to build a boat out of kelp, or whatever.

Rather, humans have incredible cultural knowledge. People learn by watching those they perceive to be successful, and over centuries societies zero in on the long list of steps required to hunt seals.

I sought out the best people to learn from. That led me first to Andy Crestodina, who led me to Rand Fishkin and Britney Muller at Moz, who led me to Bill Slawski, who led me to the actual Google patents. Joel Klettke led me to Joanna Wiebe. I browsed Coursera syllabi to find Phil Kotler and Michael Porter, and then moved to modern updates from April Dunford, Byron Sharp, and Mark Ritson.

My learning followed the same progression Henrich observes across societies, but especially in research on children. Children prefer to learn from people who they can identify as high status — except for the times when they choose people who are more similar to themselves. In learning, we “scaffold,” meaning we seek the person who can teach us the immediate next step, even if they may not be able to teach the eventual step.

Andy Crestodina is fantastic at teaching the tactics of content SEO. Rand Fishkin starts to pull in more research about how Google itself works. Bill Slawski summarizes Google patents. And the Google patents were always just sitting there, waiting to be understood.

I’ll freely admit that I started with mimicry. But eventually, by scaffolding my learning and progressing to the next depth of information, I started to understand the fundamentals of how marketing works — and, as important, the dynamics of how the field operates — to the point where I could combine ideas, put aside the paint by numbers, and start to paint.

I got very good very quickly, but it was only part of the answer

In March of 2016, I launched a website about how to use psychology to work out more consistently. My degree is in psychology and I love fitness, and I saw so many eager people shooting themselves in the foot, making exercise a dread, and quitting as a result. I figured I could put what I’d been learning into practice and help some people out along the way.

A week after the site went up, it went viral on Reddit and pulled 250,000 visitors. A month later it had gone viral twice more. After that it stopped going viral and started to accumulate traffic from Google, and these people were more likely to read and sign up for the email list. By the time I decided to stop working on it, it pulled 30,000 organic search visitors every month.

But the day I published that first post I literally shook.

My skin felt electric. I had a buzzing sensation. Intermittent hot flashes. I watched the post climb up spots on /r/fitness, saw 400 comments come in, and experienced a curious mix of joy and terror.

All-in-all, my first inkling that maybe getting good wasn’t the whole answer.

Another way that children are dumb, but feels bad to laugh at them for, is the mundane stuff they cry about.

To a kid, mistakes that adults can laugh off feel world-ending. And I think some of that is because kids are still learning about what types of actions have what types of consequences — they don’t have much experience in the world, and that makes it harder for them to judge how important or inconsequential things are.

It goes the other way too. Kids laugh at stuff that adults would never even look twice at, like when these siblings delight in smacking themselves in the face with a garbage can lid. To a child, stepping on the lever and seeing the lid move is new, it’s funny, and it’s exerting a measure of control over their environment. I can’t explain the head-smacking part.

I got much better at my job very quickly, but I was still missing the experience that tells kids when it makes sense to laugh or cry. I’ve had moments where a boss or boss’ boss or boss’ boss’ boss got angry about something I didn’t think mattered in the slightest, and I’ve gotten myself bent out of shape over stuff that they shrugged away.

I didn’t really notice this until the first time I had to disagree about something important at my current company. About 6 months into the role, still junior, I wanted to blow up a whole project — ultimately in service of making it more effective, but still by inserting myself into work that would eventually be pitched to the CEO.

When I geared up for disagreement, I was nervous. I felt a near-physical wall around me, holding me in and whispering “why would they care? It’s safer to keep your head down.”

I had spent the last two years in an environment of uncertainty. On any given day I hadn’t known whether I would be yelled at or praised or ignored, and I hadn’t realized the toll that took until I escaped to a new environment where it wasn’t true — but carried the unease along.

Now this was something closer to imposter syndrome.

With encouragement from a mentor, I put forward my idea and it went better than expected. No one questioned why I was in the room, no one asked “who even are you,” no one got offended that I dared to contradict, and I learned that the near-physical walls are not physical, and that they whisper to hold you in because they can’t stop you if you decide to tear them down.

Keeping up with the speed of the world

It’s easy to forget how much of our communication happens in idioms, and if you ever forget, kids provide plenty of examples.

Idioms at work are less blatant and have more layered meanings, but it definitely took time to appreciate that “we’re going to re-examine this item for relevance” means “this is dumb af and there’s no way we ever do it.”

I didn’t understand the layers of the onion at my first job. When clients said they would “think about it,” I didn’t appreciate that as a pretty clear “no.” And when I switched from agencies to tech, a lot of the language changed, the dynamics of the business changed, and I had to learn all over again.

Now that I finally have begun to understand, everything has started to slow down. Not literally. The world moves at the same speed it always has, but I no longer feel like I’m catching up, like I’m watching a movie with the sound off and keep missing the subtitles. I can anticipate what will happen next, where the next fire drill will come from — or at least when the drill starts I know where to look for the source of the fire.

I’m sure five-years-from-now me would reach out, tousle my bald head, and say “oh you sweet summer child,” but in fairness that’s also what today me would say to me from five years ago. It’s a young person’s game to knock the value of experience, but as time has passed I’ve begun to realize that it takes experience to unlock knowledge, and that even now there is knowledge I am waiting to use, because I don’t have the experience to apply it.

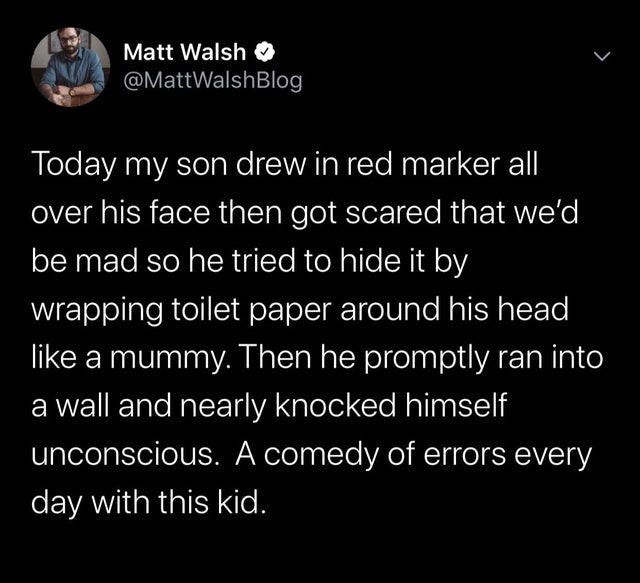

All of this to say, I see the world in real time. I know enough to not panic when I cover my face in red marker, and hopefully before long I’ll learn to stop with red markers altogether. The floating pressure is removed. I learned how to hunt the seal. The walls have stopped their whisper. When I set out to “git gud,” I didn’t realize it would be only part of the answer, but with time the other parts have begun to fall into place like the best game of Tetris I’ve ever played.